From PPO to GRPO: The Evolution of Fine-Tuning for Reasoning Models

Reinforcement learning is critical in fine-tuning LLMs to align with human intent (RLHF) and to bootstrap reasoning capabilities using self-verifiable tasks (RFT), which then generalize to complex problem-solving across domains. For years, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) was the standard algorithm for policy optimization[1][2]. However, as models scaled and the focus shifted towards reasoning capabilities (Math, Code), the computational cost of PPO became a bottleneck. Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO), introduced by DeepSeek[3], elegantly eliminates the need for a memory-intensive "Critic" model while stabilizing training for complex reasoning tasks.

This post summarizes the algorithm evolution from PPO to GRPO, along with recent improvements on GRPO, and also compares their real-world applications.

1. The Foundation: PPO and InstructGPT #

Original PPO (The "Actor-Critic" Standard) #

PPO, introduced by OpenAI in 2017[1], belongs to a family of reinforcement learning methods known as Actor-Critic algorithms. Before diving into PPO specifics, let's understand this foundational paradigm[4].

The Actor-Critic Framework #

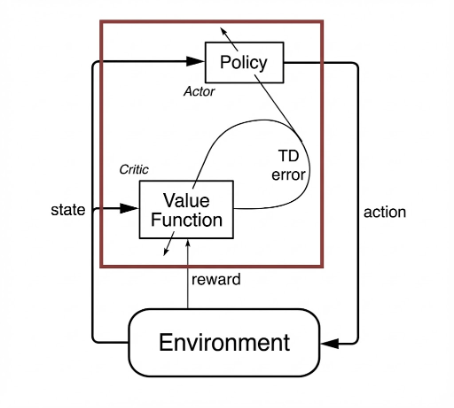

Actor-Critic algorithms combine two complementary components that work together to learn optimal behavior, as illustrated in Figure 1:

-

Actor (Policy, ): The decision-maker that observes the current state and selects actions. It learns what to do in each situation by adjusting its policy parameters based on feedback.

-

Critic (Value Function, ): The evaluator that estimates the expected cumulative future reward from a given state. It learns how good a state is, providing a baseline for assessing whether the Actor's actions are better or worse than expected.

The interaction loop works as follows: the Actor takes an action in the environment, receives a reward, and transitions to a new state. The Critic then evaluates this outcome by computing the Temporal Difference (TD) error—the difference between the actual reward plus the estimated value of the next state, and the previously estimated value. This TD error becomes the training signal: a positive error means the action was better than expected (reinforce it), while a negative error suggests the action was worse (discourage it).

The key insight is that the Critic's value estimates reduce variance in policy gradients. Without a Critic, we would need to wait until the end of an episode to assess action quality using total returns, which introduces high variance. The Critic provides immediate, learned feedback at each step.

PPO: Proximal Policy Optimization #

PPO implements the Actor-Critic framework with a crucial innovation: clipped surrogate objectives that prevent destructive policy updates. In the context of LLM alignment:

- The Actor is the language model () generating text token by token.

- The Critic is a separate Value Model () estimating the expected reward for a given prompt-response state.

The Critic enables the calculation of advantage using Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE)[5], which measures how much better a specific action was compared to what the Critic expected—providing a low-variance training signal for the Actor.

The InstructGPT Recipe #

When OpenAI scaled this for ChatGPT (InstructGPT)[2], they defined a specific reward objective to balance "helpfulness" with "alignment". The reward for a prompt question and completion output is defined as:

This is the per-token reward formulation with the KL divergence penalty, where:

- : The score from the trained Reward Model.

- KL Penalty: The second term ensures the model doesn't drift too far from the initial Supervised Fine-Tuned (SFT) model (), preventing "reward hacking".

The original instructGPT paper also have a third term that adds a standard language model loss from pretraining (next token prediction) to the gradient updates to prevent model from forgetting how to write normal output while it chases reward scores (the "alignment tax"). This third term is not commonly adopted in most follow up work since KL penalty is good enough for regularization and this pretraining term actually requires more compute for extra pretraining batch and often leads to slow convergence since alignment and pretraining are fundamentally two contradicting goals.

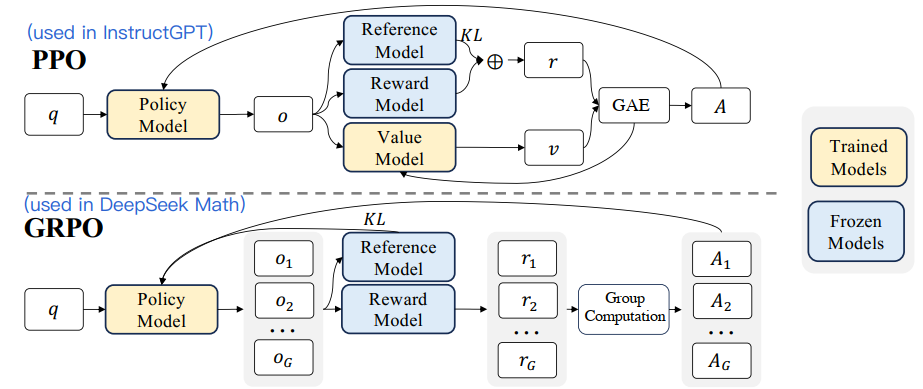

The full PPO algorithm to align the GPT model is depicted in upper part in Figure 2. In addition to the reward objective described in Equation (1), it also trains a Value Model along with the Policy Model. The Value Model estiamtes the value of an output and is used to calculate the advantage (how much better this specific response was than expected) in the Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE)[5] component to get advantge (conceptually ). With this, we arrive the overall surrogate objective for instructGPT:

where and are current and old policy models, and , are questions and outputs sampled from old policy model. is the importance sampling ratio to adjust for the fact all samples are observed with old policy model.

While effective, this PPO algorithm is expensive. Training a Value Model (often as large as the Policy Model) essentially doubles the memory and computational burden. Another subtle point is that the value model is treated as a baseline in the calculation of the advantage for variance reduction. While in the LLM context, usually only the last token is assigned a reward score by the reward model, which may complicate the training of a value model that is accurate at each token.

2. The Innovation: GRPO (DeepSeekMath) #

The DeepSeekMath paper proposed Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) to eliminate the Critic (i.e. the Value Model) entirely to allievate the two above mentioned inefficiencies for PPO.

Instead of training a Value Model to predict the baseline, GRPO uses the statistical properties of a group of outputs to estimate the baseline.

For every prompt q, the model samples a group of outputs (e.g., G=64) from the old policy , yielding G rewards . The advantage for each output is calculated by normalizing its reward relative to the group average:

This group relative comparison implicitly serves as a baseline: if an answer is better than the group average, it gets a positive advantage; otherwise, it gets a negative one. With this settings, we can have the surrogate objective for GRPO:

where

For the KL divergence penalty, different from the KL penalty term used in Equation (1), we estimate the KL divergence with the following unbiased estimator[6]:

Derivation of the Unbiased KL Estimator (click to expand)

Let's denote and only consider the function inside the expectation in Equation (5). The initial KL divergence becomes with expectation over samples from (strictly speaking, samples come from , not — we cover this correction in DeepSeek V3.2 later).

The key insight for variance reduction: add something with zero expectation and is negatively correlated with the existing term. Since has expectation 1 (as follows ), we add which has zero expectation and is negatively correlated with .

This gives us . To find optimal , we'd minimize variance, but this yields an intractable expression depending on and . Instead, we use the constraint that KL divergence must be non-negative. Since is concave and , choosing guarantees positivity: .

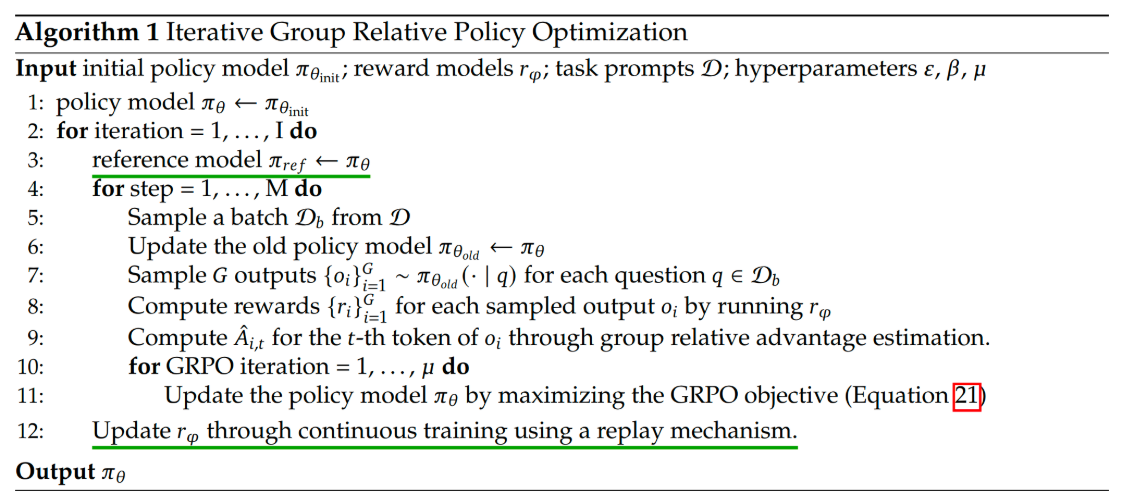

The paper details an iterative version of GRPO, which updates the reference model and reward model periodically to handle distribution shifts as shown in Figure 3.

3. The Refinement: DeepSeek V3.2 Improvements #

While GRPO was efficient, the DeepSeek V3.2 paper[7] identified instability issues in the original implementation, specifically regarding the KL divergence calculation.

The Problem: Biased Estimation #

In the original implementation in DeepSeek Math[3], the KL divergence was approximated using samples drawn from the old policy (), but it was used to update the current policy () without correcting for the distribution shift using importance sampling ratio. This introduced bias, especially when the current policy drifts far from the reference, leading to noisy gradient updates and slow training convergence or even instability.

The Solution: Unbiased Importance Sampling #

DeepSeek V3.2 introduced an unbiased KL estimator by explicitly incorporating the importance sampling ratio into the KL calculation:

Why this matters:

- Eliminates Systematic Error: The gradient of this estimator is unbiased, ensuring that the optimization direction is mathematically valid even when the policy shifts.

- Stability: If the model assigns a very low probability to a token (which would normally blow up the KL penalty), the importance sampling ratio also becomes small, effectively dampening the gradient and preventing numerical explosions. This facilitates stable convergence.

Why use importance sampling adjustment? Why not approaches like Doubly Robust (DR)? (click to expand)

First of all, the adjustment with important sampling is mathematically mandatory to fix the distribution shift in current policy and old policy (i.e. ).

Secondly, why not use other popular algorithms like DR to achieve low bias low estimator? Let's first understand the DR algorithm. The estimator combines a model (low variance, high bias) with observed reward (high variance, low bias):

Key features of a DR estimator:

- Baseline: It starts with the value predicted by your Critic model ().

- Correction: It looks at the residual error (), which tells you how much the reality () differed from the prediction.

- Weighting: It scales this error by the importance sampling ratio ().

The estimator remains mathematically unbiased if either one of these two conditions is met:

- The Model () is accurate (even if is wrong).

- The Importance Sampling ratio () is accurate (even if the Model is garbage).

In GRPO case, calculating requires training a Value Model (Critic), which GRPO explicitly removes to save memory. Therefore, model-based DR is not really applicable.

In addition to unbiased KL estimation, the DeepSeek V3.2 paper also introductes other improvement on RL proces such as off-policy sequence masking, keep routing, and kep sampling mask. It is another solid tech report that was careful reading.

Summary Comparison: PPO vs. GRPO #

This table summarizes the key aspects of both PPO and GRPO algorithms and evolution of GPRO as we discussed above.

| Feature | PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) | GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Actor-Critic: Uses a learned Value Model (Critic) to reduce variance | Group-Relative: Uses the statistical mean of a group of outputs as the baseline |

| Model Requirements | High: Policy Model + Value Model (approx. 2x memory) | Low: Policy Model only (Value Model removed) |

| Baseline Estimation | Predicted by the Value Model | Calculated from group statistics: |

| Advantage Formula | (GAE) | |

| Compute Efficiency | Lower (updates 2 massive models) | Higher (updates 1 model) |

| KL Divergence | Usually applied as a penalty to the Reward | Applied as a loss term (V3.2 adds Importance Sampling) |

| Best For | General alignment, continuous control, small batch environments | Mathematical reasoning, coding, scenarios where group consensus matters |

4. The Generality Gap: When to use GRPO or PPO? #

While GRPO is a breakthrough for efficiency in Large Language Models (LLMs), it is not a universal replacement for PPO in general Reinforcement Learning. Its structural reliance on "Group Sampling" creates strict limitations.

Limitation 1: The Requirement for Resettable States GRPO calculates its baseline by averaging G outcomes from the exact same state. This works perfectly for LLMs because we can feed the same prompt into the model 64 times in parallel.

GRPO's Problem: In many real-world RL scenarios—like physical robotics, stock trading, or live user interactions—you cannot "undo" reality to try 63 other actions from the exact same millisecond. The state is transient and non-resettable.

PPO's Advantage: PPO's Value Model () learns to generalize. It can see a state once, estimate its value, and apply that knowledge to similar future states without needing immediate parallel samples.

Limitation 2: Sample Efficiency in Exploration Because GRPO only compares an action against its "siblings" in the current group, it lacks a global perspective on value.

The Risk of "Mediocre Plateau": If all 64 samples in a group are bad, the slightly-less-bad one gets a positive reward (normalized advantage). The model might optimistically reinforce a mediocre action just because it was the "best of a bad bunch."

PPO's Advantage: A trained Value Function has a "global memory." If it knows a state is bad (Value = -10), even the best action in that state might still have a negative advantage if it doesn't improve the situation enough. This helps PPO navigate out of local optima more effectively in continuous control tasks.

How Should We Choose?

Use GRPO When: You are doing "System 2" reasoning (Math, Code, Logic) where you can easily simulate/sample many parallel futures for a static input prompt.

Use PPO When: You are interacting with a dynamic environment (Robotics, Games, Live Systems) where you cannot reset the state, or when sample efficiency is more critical than memory efficiency.

5. Applications and Use Cases #

PPO: The Generalist Alignment Tool #

PPO remains the robust standard for general-purpose RLHF, particularly for:

- Chatbot "Vibe" Checking: Aligning tone, safety, and helpfulness (e.g., Llama 3, GPT-4).

- Subjective Tasks: Where there is no single "correct" answer, but rather a preference ranking (e.g., creative writing, summarization). The learned Value function helps smooth out the noise in subjective human feedback.

GRPO: The Specialist Reasoning Tool #

GRPO has emerged as a superior choice for "System 2" thinking tasks:

-

Mathematical Reasoning: As showcased in DeepSeekMath, sampling 64 outputs allows the model to explore diverse reasoning paths. The group relative signal rewards the paths that lead to the correct answer more efficiently than a standard value function could predict.

-

Code Generation: DeepSeek V3.2 utilizes GRPO for "Agentic Coding" tasks. The ability to verify code execution (pass/fail) makes the group comparison highly effective.

The "Alignment Tax" vs. "Reasoning Power" #

An interesting angle to compare them is their impact on model capabilities:

-

PPO is often associated with the "Alignment Tax,"[2] where the model becomes safer but potentially less capable at reasoning because it is constrained by a Critic model that tries to predict the average human rater's preference (which might be flawed or biased).

-

GRPO encourages Self-Verification. By comparing against its own group of outputs, the model effectively learns to "beat its own average". In domains like Math or Code, where ground truth exists (the code runs or it doesn't), GRPO allows the model to climb the capability ladder purely through exploration and self-correction, without being held back by a potentially inaccurate Value Model critic[3].

Acknowledgement #

Thank you Li Tan and Shen Zhu for carefully reviewing the draft.